Sukkot marks the autumn harvest time. It is a festival devoted to thanksgiving for the abundance of life. In ancient times, the final agricultural harvest took place in the beginning of the autumn and following the intensely busy work of harvesting people would celebrate their abundance and give thanks to God. In time, the festival of Sukkot came to be associated with the Forty Years of Wandering in the Wilderness, as well. Since crops must be harvested quickly, once they ripen, farmers often built for themselves small temporary booths out in their fields so that they could take advantage of every minutes of daylight once the crops were ready to be picked. These temporary booths were associated with the temporary shelters built by our ancestors after they left Egypt when, for 40 years, they wander through the wilderness of Sinai, before entering the Land of Israel.

Jewish tradition teaches that the earth and everything in it belongs to God. We humans are not the owners; God owns the world. We are the caretakers and as such, as are privileged to enjoy the bounty of the earth. On Sukkot we give thanks to God, the source of our sustenance and the bounty of the agricultural season. In ancient times, a good harvest bespoke survival for the winter. A small harvest spelled hunger; severe drought spelled famine. Many of us are sheltered from the effects of drought and poor harvests, and we buy much or all of our food in a supermarket which is perpetually fully stocked. Hence we are not acutely aware of the connection between the natural world, God, and our nutrition as were our ancestors. Sukkot becomes all the more important for it reminds us of these connections and sensitizes us to the needs of those in the world whose food is not readily available at the neighborhood supermarket and who suffer from droughts and famines caused by changes in weather. Our responsibility to feed them is reinforced by the Jewish teaching that the world belongs to God; we, the caretakers, must take care of one another.

On Sukkot, we build small temporary dwellings called sukkot. A sukkah has at least three sides and the roof is an open lattice work covered with cut branches from trees through which the stars can be viewed at night. The Torah commands: You shall live in huts seven days; all citizens of Israel shall live in huts, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in huts when I brought them out of the Land of Egypt, I the Lord your God. [Leviticus 23:42-3] Tradition holds that one "lives" in the sukkah during the week of Sukkot, which means that people eat as many meals as possible there and also socialize, tell stories, and sing songs there. Some people sleep out in their sukkot if weather permits. A sukkah may be made of wood, metal, or even PVC piping, and is decorated with symbols of the season. When I was a child, we hung fruits and vegetables from the ceiling, but many feel that wasting good food is inappropriate. A fine alternative is to hang plastic fruits and vegetables and donate tzedakah (charity) to an organization dedicated to feeding hungry people.

On Sukkot, we build small temporary dwellings called sukkot. A sukkah has at least three sides and the roof is an open lattice work covered with cut branches from trees through which the stars can be viewed at night. The Torah commands: You shall live in huts seven days; all citizens of Israel shall live in huts, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in huts when I brought them out of the Land of Egypt, I the Lord your God. [Leviticus 23:42-3] Tradition holds that one "lives" in the sukkah during the week of Sukkot, which means that people eat as many meals as possible there and also socialize, tell stories, and sing songs there. Some people sleep out in their sukkot if weather permits. A sukkah may be made of wood, metal, or even PVC piping, and is decorated with symbols of the season. When I was a child, we hung fruits and vegetables from the ceiling, but many feel that wasting good food is inappropriate. A fine alternative is to hang plastic fruits and vegetables and donate tzedakah (charity) to an organization dedicated to feeding hungry people.

For a picture of the award-winning MIT Hillel sukkah, click here.

The tradition of Ushpizim is a charming custom by which families symbolically invite the patriarchs and matriarchs to visit their sukkot each day of the festival as an honored guest. It is also traditional to invite friends and relatives to share a meal in the sukkah.

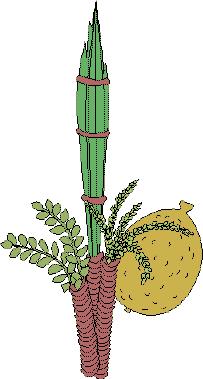

The Torah instructs us to take up four species in hand to celebrate Sukkot. On the first day you shall take the product of the goodly trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God seven days. [Leviticus 23:40] The first three (willow, palm, and myrtle) are bound together and collectively called a lulav. The fifth is the etrog (citron), a sweet smelling citrus fruit grown in Israel. It is held with the lulav and brought both to the synagogue where it is waved as Hallel is recited. The lulav and etrog are also waved in the sukkah. Ancient Israel was first and foremost an agricultural society and the laws, customs, and rituals described in the Torah reflect this. The four species symbolize the agricultural abundance of the land and God's role in nourishing Israel. During the time when the Temple stood in Jerusalem, the four species were used daily in the Temple during Sukkot. After the Destruction of the Second Temple, the four species were used as part of the synagogue ritual, waved during Hallel (specifically, while reciting Psalm 118), only on the first day by biblical ordinance, but the rabbis decreed that it should be brought to the synagogue every day during Sukkot with the exception of Shabbat, when the prohibition against carrying took precedence. One holds the lulav in one's hands with the palm fronds facing forward, the willow on the left and the myrtle on the right and the etrog on top, tip pointing downward. Together, the four species are shaken in six directions during Hallel, signifying that God is found everywhere. It is considered a mitzvah to acquire the most beautiful lulav and etrog available in order to honor the holy day.

The Torah instructs us to take up four species in hand to celebrate Sukkot. On the first day you shall take the product of the goodly trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God seven days. [Leviticus 23:40] The first three (willow, palm, and myrtle) are bound together and collectively called a lulav. The fifth is the etrog (citron), a sweet smelling citrus fruit grown in Israel. It is held with the lulav and brought both to the synagogue where it is waved as Hallel is recited. The lulav and etrog are also waved in the sukkah. Ancient Israel was first and foremost an agricultural society and the laws, customs, and rituals described in the Torah reflect this. The four species symbolize the agricultural abundance of the land and God's role in nourishing Israel. During the time when the Temple stood in Jerusalem, the four species were used daily in the Temple during Sukkot. After the Destruction of the Second Temple, the four species were used as part of the synagogue ritual, waved during Hallel (specifically, while reciting Psalm 118), only on the first day by biblical ordinance, but the rabbis decreed that it should be brought to the synagogue every day during Sukkot with the exception of Shabbat, when the prohibition against carrying took precedence. One holds the lulav in one's hands with the palm fronds facing forward, the willow on the left and the myrtle on the right and the etrog on top, tip pointing downward. Together, the four species are shaken in six directions during Hallel, signifying that God is found everywhere. It is considered a mitzvah to acquire the most beautiful lulav and etrog available in order to honor the holy day.

Why four species? Why not three or five? While I cannot provide an academic answer to this question, there are many wonderful drashot (homiletical explanations) for the number four. Perhaps the best known is that there are four types of Jews: the etrog, which possesses both taste and fragrance symbolizes those who possess both learning and good deeds. The palm branches possess taste but no fragrance, symbolizing those who possess learning but do not perform good deeds. The myrtle is the inverse of the palm, possessing no taste but having a pleasant fragrance; this is likened to those who are not learned but do good deeds. Finally, the willow has neither taste nor fragrance, symbolizing those who possess neither learning nor good deeds. We, of course, with to be the etrog, possessing both learning and good deeds. But the reality of life is that our communities are made of all four types of people and because community is such a high priority in Judaism, we bind all four species together, as we ought to bring together all Jews in one community.

Another famous interpretation of the four species likens each to a body part: the etrog is the human heart; the palm fronds are the spine; the myrtle is the eyes; the willow is the mouth. Just as one waves all four species before God on Sukkot, so too one uses all the parts of one's body to worship and serve God: heart, spine, eyes, and mouth.

The book of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) is traditionally read during the festival of Sukkot on Shabbat Chol Ha-Moed (the intermediary Shabbat of Sukkot). The theme of Kohelet, a biblical book ascribed to King Solomon, is that physical possessions and pleasures are transitory and therefore of limited meaning, while living properly and serving God has ultimate value. The unsubstantial sukkah reminds us of our vulnerability and this reminds us of the transitory nature of physical life on earth. Our learning and deeds are the most important accomplishments we can pass on.

Spending time in a sukkah intesifies our awareness of just how fragile life is and that our lives are inextricably interwoven the rest of nature. Without a solid ediface to protect us from the elements, and exposed to the immensity of the universe, we are sensitive to our mortality and our connection to the universe. Sitting in our self-contained homes, we can often forget the rest of the world and certainly ignore the natural world for long periods of time. In the Sukkah, we feel part of that world. We are not sheltered from rain, wind, the sounds of the animals about us; we cannot compensate for temperature, light (except with a lantern on the table) or noise. For many people, being outside is a deeply spiritual experiece and for them, Sukkot is an ideal festival because among all the Jewish festivals, it goes the farthest to emphasize our connection to nature.

Living in a Sukkah for a week (even if we simply take a few meals there, spend some time reading and studying, and perhaps sleep one night in it, we can gain insight into the question of what a human "needs" to live. The Sukkah is the epitome of simplicity; it offers no luxuries and not even a modicum of protection. There are several messages we might glean from this experience: First, that there is value to simplifying life. If we spend less time with our appliances and conveniences (and the time required to maintain them) we have more time for people, study, and contemplation. Second, living in a Sukkah can serve to remind us that there are many people in the world who have no more protection than a Sukkah affords; we have a responsibility to rectify that situation through tzedakah.

Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav penned the prayer below. For him, time spent alone in nature was a deeply moving spiritual experience; he found the woods an ideal venue for finding God. So, too, for many of us. I offer this prayer for you to recite in a Sukkah, or on your next camping venture.

Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav's Prayer

Master of the universe, grant me the ability to be alone;

may it be my custom to go outdoors each day,

among the trees and grasses, among all growing things,

there to be alone and enter into prayer.There may I express all that is in my heart,

talking with God to whom I belong.And may all grasses, trees, and plants awake at my coming.

Send the power of their life into my prayer,

making whole my heart and my speech

through the life and spirit of growing things,

made whole by their transcendent Source.O that they would enter into my prayer!

Then would I fully open my heart in prayer, supplication, and holy speech;

then, O God, would I pour out the words of my heart before Your presence.

The Jewish Holidays: A Guide & Commentary by Michael Strassfeld (Harper & Row).

The How To Handbook for Jewish Living by Kerry M. Olitzky and Ronald H. Isaacs (Ktav).

It's a Mitzvah! by Bradley Shavit Artson (Behrman House and the Rabbinical Assembly).

Jewish Family & Life by Yosef I. Abramowitz and Rabbi Susan Silverman (Golden Books).

The Kid's Catalog of Jewish Holidays by David Adler (Jewish Publication Society).

Seasons for Celebration by Rabbi Karen L. Fox and Phyllis Zimbler Miller (Perigee Books).